Being suspended from school or sent to the office is tied to a big drop in grade point average (GPA), especially for Black and Latinx children, according to UC San Francisco researchers.

Being suspended from school or sent to the office is tied to a big drop in grade point average (GPA), especially for Black and Latinx children, according to UC San Francisco researchers.

Their study, published Oct. 20, 2023, in JAMA Network Open, analyzed the school records of 16,849 students in grades 6 through 10 in a large urban school district in California from 2014 to 2017. Black students who had an “exclusionary school discipline” (ESD) event — being removed from a classroom or suspended — in 2014 to 2015 saw an average drop of 1.44 points in their GPA by the end of the three-year study.

Latinx students saw a drop of 1.39 points and American Indian/Alaskan Natives saw a drop of 1.33 points after three years if they were suspended or sent from class in 2014 to 2015. The average GPA decline across all students who experienced an ESD in the 2014 school year was 0.88 points after researchers controlled for race, ethnicity, maternal education, gender, age or whether the student had an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) for disabilities.

Black children were 10 times more likely to experience an ESD event than white students, and Latinx students were three times more likely. The school district studied doesn’t allow expulsions, so there were none to examine.

“ESDs hurt all those who experience them, but they drastically hurt those from minoritized groups, and particularly Black and Latine communities,” said Meghan D. Morris, PhD, UCSF associate professor in epidemiology and biostatistics and senior author of the study. “These events are another way of reinforcing the systems of racism that already occur within the classroom and the school environment and the community environment more broadly.”

Because ESDs reflect embedded racism, they should be considered adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) that put students at greater risk for chronic illnesses like diabetes and asthma, as well as mental illness, said Camila Cribb Fabersunne, MD, first author and UCSF assistant professor of pediatrics.

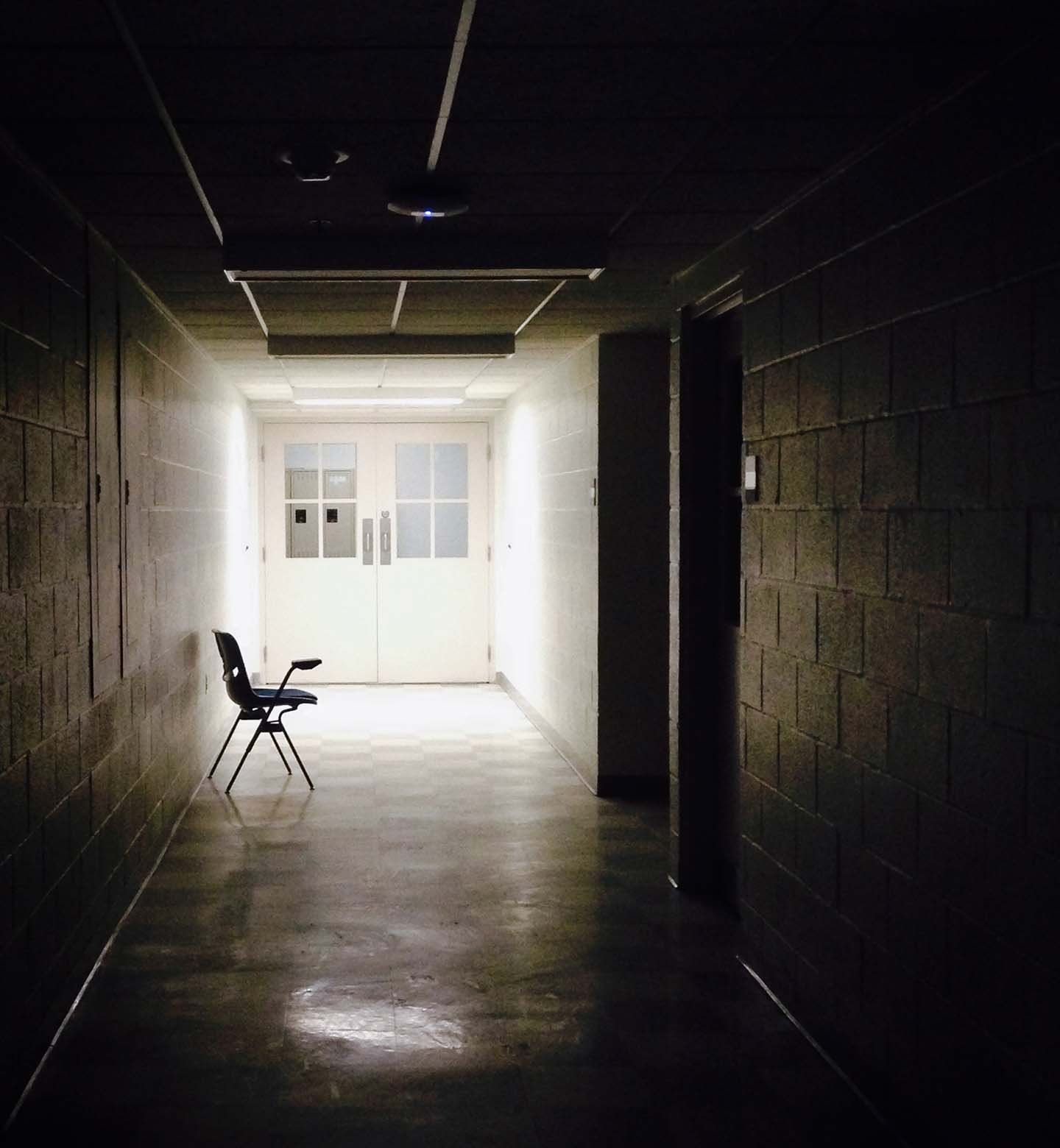

“These children are experiencing discrimination in how school discipline is applied,” said Cribb Fabersunne. “When students are subject to trauma in a place that should be a sanctuary — a place where they think they will be safe from racism and the adults will support them — it impacts them in a profound way.”

The power of the white coat

Just as pediatricians screen for attention issues and learning disabilities during health care visits, they must screen for ESDs by asking patients whether they have been sent home or expelled from school — and intervene if so, Cribb Fabersunne said.

“Pediatricians should call the school and ask the assistant principal why the disciplinary action was taken,” Cribb Fabersunne said. “They should explain that the student’s behavior may reflect difficult things going on outside of school, and that practices like restorative justice and mindfulness are more effective responses.”

Black and Latinx students are suspended at higher rates compared to white students, and receive harsher punishments for similar behaviors. Past research shows ESDs don’t prevent classroom disruptions; in fact, they are linked to more disruptions, exclusion by peers and truancy. In adulthood, children who experienced ESDs are more likely to be incarcerated. GPA, meanwhile, indicates educational attainment, which research has shown to be key to socioeconomic opportunity in adulthood, the authors wrote.

Pediatricians should encourage schools to adopt positive, non-exclusionary practices to address student behavior, such as meditation, social-emotional skills training and restorative justice, which emphasizes problem solving and cooperation to heal and prevent harm to others. In addition, pediatricians should be advocating to increase the funding and support that schools receive to provide trauma-informed socio-emotional support services.

“I don’t think pediatricians are enraged enough. If we want health equity, we need to advocate on the individual, school and local level, because these disciplinary practices are widespread and hurt our patients, and that is going to harm their health,” said Cribb Fabersunne. “The power and privilege of the white coat is real, and we should use it for good.”

Authors: In addition to Morris and Cribb Fabersunne, authors include Seung Yeon Lee, independent researcher; Danielle McBride, UCSF Department of Medicine; Ali Zahir, UCSF Department of Neurology; Angela Gallegos-Castillo, Instituto Familiar de la Raza Inc.; and Kaja C. LeWinn, UCSF Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health Sciences.